http://bugzilla.gnome.org/show_bug.cgi?id=628195

EDIT: some people have been asking for a better screenshot (there’s only two pixels of difference above). Here’s a highly exaggerated example:

http://bugzilla.gnome.org/show_bug.cgi?id=628195

EDIT: some people have been asking for a better screenshot (there’s only two pixels of difference above). Here’s a highly exaggerated example:

Live extension enabling and disabling has landed! This allows users to do this!

I could do that all day. It’s quite fun.

But there’s one little problem. Extension developers? We need to talk.

“What did I do?”

Nothing bad, I promise. You just have a new responsibility: in case the user doesn’t like the extension, you need to undo all the changes that you ever made to the shell. Make it look like your code never touched the place. Otherwise: that video above? The giant illusion will drop to the ground and crack into a thousand pieces. Like that China I broke last weekend.

“Uh, OK. How?”

If your extension looked like this before, you need to make it look like either this, or this.

Put simply: main(), uh, how do I say this? main() has been, uh, let go. Sure. Don’t worry though, he’s been replaced with init(), enable() and disable(). They’re just as cool. I promise. The in-depth obitua — uh, termination notice can be read here. init()‘s best friend, the “helper” object couldn’t make it for this trip. He’ll be here next year.

There’s three simple rules to take into account:

main(). This has been removed. It has been replaced with a new hook, init(). You should use init() to initialize any state. Do not modify the Shell inside of this function.init() may return an object, called the “state object”. If you do not return an object, the module is considered the state object. This object is supposed to have two new methods: enable() and disable(). These should modify Shell in the appropriate way. For lack of better vocabulary, extensions which use the module (return nothing from init()) as their state object are called “stateless” objects, and those which don’t are “stateful”.init() is guaranteed to be called at most once per shell session. enable() and disable() may be called at any time. If your extension is enabled at the start of the session, enable() will be called. If your extension is disabled at the start of the session, disable() will not be called, and there is no guarantee that init() will be called.Additionally, keep in mind that Shell extensions are versioned, so only extensions that are targeted for 3.2 should port to the new API. Some extensions that want to support both 3.0 and 3.2. Fortunately there is an easy way to do exactly that. Just run init(), and then enable():

function main() { init(); enable(); }

… Stateful extensions just need to run enable() on their state object.

function main() { init().enable(); }

Oh, and one last thing. Thank you. You don’t have to believe it, but I’m doing this for you. I’m trying to make it easier for users to safely try out your awesome work. There’s more awesome stuff for you guys on the way. I promise.

Today is an exciting day for GNOME 3.0! Why? Invisible borders have landed! What does this mean for you? One pixel borders are no longer! No more pixel hunting! The last remnants of the cursor accuracy kingdom have been tore down! Pointer precision, you are —

“What?”

Let me draw you a picture.

In GNOME3 before today, if I wanted to conveniently resize a window, I had to hunt for one-pixel borders. I would finally get my mouse positioned right on the border, and then carefully click…

and then miss… So, it’s not surprising people are upset about this. Now, you can go outside the actual visible part of the window, and still resize it!

Now, you have as much space in the world to resize your windows: we extend the resizable area to outside of the actual window. Additionally, the mount of area that is available to resize is a user preference, and completely customizable! That is, the green area in the picture below is completely customizable by a gconf setting.

Now, you have as much space in the world to resize your windows: we extend the resizable area to outside of the actual window. Additionally, the mount of area that is available to resize is a user preference, and completely customizable! That is, the green area in the picture below is completely customizable by a gconf setting.

The way I did this was by making every X window a little larger, and use Owen’s existing shaping code to hide the excess area around the borders. This means that toolkits that use the parent window’s size to find their visible extents are now going to break. Use the _NET_FRAME_EXTENTS X atom as a replacement.

Oh, and since I’m using Owen’s existing shaping code, and that uses an 8-bit mask to hide the shaped region, this made it quite a bit easier to add a feature that people have been begging for for a little while: antialiased borders. This hasn’t landed quite yet, but it should be coming soon enough!

Next time, I’ll talk about SweetTooth some more!

I’ve been tinkering with web development a lot lately as part of my work with SweetTooth, the GNOME Shell extensions repository I’m working on for GNOME.

At the suggestion of Vinicius Depizzol, who’s been doing a wonderful job redesigning the GNOME web sites, I tried my hand at creating a Shell-like switch widget to allow a user to click a button to turn extensions on and off. Using some precious combination of JS and CSS, I’ve finally made a switch widget I think looks nice. Go ahead: grab it, click on it, fling it around, try and break it! It should just feel “right”.

Figuring out whether the widget is activated and setting the appropriate style classes, the drag logic, and figuring out where to put the switch handle are the only responsibilities of the JS code: everything else is done with CSS, using a combination of border-radius, position: absolute, floats. The triple-line on the grab handle is “drawn” with CSS and manipulates the border styling properties to do its bidding. The animations to fade the background-color and slider position are all CSS3 transitions.

There’s still one unsolved problem, which is the flash and fade of the background color when loading the page, and as much as I tried, I couldn’t solve it. It’s a fallout from CSS thinking it has transitioned from one class to another, but in actuality, it’s just jQuery adding a style class after the node has been constructed. Feel free to yell at me I’m being stupid.

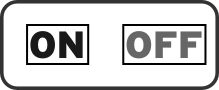

As usual, the hard part in concocting something like this is compatibility. The web truly isn’t meant for something pixel-perfect like this, and it shows. Browsers like IE, where compatibility is usually a pain, weren’t involved at all here (I haven’t bothered to test them — again, yell at me). Through poking people on IRC, I found that OS X has different font metrics for the “ON” and “OFF” labels

(A mini rant to the CSS WG: why can’t I create a new flow root/block formatting context to contain floats by asking for one, instead having to rely on the side effects of other properties?)

Originally, the DOM looked like this image to the left, if you forget about the switch handle. That is, there were two sub elements that were absolutely positioned inside the switch: the switch was hardcoded to a 64px width. Here, everything worked fine and the code was relatively simple.

Originally, the DOM looked like this image to the left, if you forget about the switch handle. That is, there were two sub elements that were absolutely positioned inside the switch: the switch was hardcoded to a 64px width. Here, everything worked fine and the code was relatively simple.

The problem was that on some browsers and platforms, the text metrics are inconsistent. Unfortunately, the HTML specification gives no guarantee about text measurement, explicitly stating it to be agent-specific. I could deal with this, but ti would be nice if CSS had relative units for glyph widths or JS let you get at some arbitrary measurements of text. <canvas> lets you get at a TextMetrics object, but the only current attribute there is width. For instance, even though I included a web font, WebKit on Mac (which uses CoreGraphics) looked terrible.

Just to make me more irritated, a normal font-weight made it work perfectly, and was almost pixel-perfect to the way bold looked on every other browser/OS. “Go eat a ham”, said Apple. So, obviously, I can’t rely on things which aren’t meant to be relied on.

Just to make me more irritated, a normal font-weight made it work perfectly, and was almost pixel-perfect to the way bold looked on every other browser/OS. “Go eat a ham”, said Apple. So, obviously, I can’t rely on things which aren’t meant to be relied on.

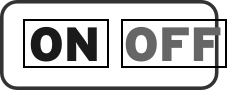

Welp. So, using some complicated trickery using width: 50%, floats, float containment, I finally got a DOM I wanted, and should hopefully be a bit more flexible. This one should make the box stretch in accordance to font weights and such: float containment means that the parent will expand to the container, and width: 50% means that the children will expand to fill half their container. Perfect.

Welp. So, using some complicated trickery using width: 50%, floats, float containment, I finally got a DOM I wanted, and should hopefully be a bit more flexible. This one should make the box stretch in accordance to font weights and such: float containment means that the parent will expand to the container, and width: 50% means that the children will expand to fill half their container. Perfect.

I simultaneously love and hate web development because of things like this.